House of Cards: The Politics of Calling Card Etiquette in Nineteenth-Century Washington

Merry Ellen Scofield

In the early republic, social media had its own crucial importance, although what the media employed was not the tweet, but little bits of pasteboard.

Social media has dramatically changed the nature of contemporary presidential campaigns. In a way, that is nothing new. In the early republic, social media had its own crucial importance, although what the media employed was not the tweet, but little bits of pasteboard.

The calling card of Thomas Jefferson, Minister to France, 1784-1789. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

In 1830, it was sometimes called carding, and considered by one Washington diplomat to be a highly efficient invention. Gone, he wrote, was the “genuine old fashioned mode of visiting” in which one sent personal messages, knocked on doors with one’s own knuckles, or sat to tea with those one called upon. Now, with the convenience of calling card etiquette, those who wished “to inform their friends that they are still alive” or be on “visiting terms” with the others who composed capital society, needed only to circle the city by carriage, dropping off cards at the doors of people one often “did not care six pence about,” and without ever taking the trouble to inquire whether Mrs. A or Mr. B were at home.

The diplomat exaggerated when he implied that capital carding was either new or unique to Washington. Calling cards were in common usage by the nineteenth century, across America, throughout Europe, and into China. Men and women in communities large and small centered their social life on “little bits of pasteboard,” with women, particularly in America, taking on the brunt of the responsibility. But the diplomat’s focus on Washington came from a position of truth, for as he and anyone who had ever participated in capital society well knew, in no other city—anywhere in the world—was the making of calls and the dropping of cards taken more seriously or practiced more assertively than in the nation’s capital.

“Great importance is attached in Washington to the making and receiving of visits,” wrote one nineteenth-century social arbiter. “This does not arise simply from a love of punctilio or from the gregarious instinct of the human race. It has its root in the conviction that society is the handmaid of politics, especially in a capital city. A mighty game is being played there, which reaches out to all parts of the civilized world.” Washington’s women were in charge of that game. They played it well, having honed their craft in cities across the world before coming to the capital as the wives and daughters of diplomats, congressmen, and other federal officials, and they did so, there and elsewhere, wrote Britain’s Leonore Davidoff, “with the same spirit of competition which aggressive men display in business.” Davidoff, however, argued that nineteenth-century American society “did not intermesh with politics,” and so the women who ran that society had no “access to real power.” But Washington politics did not end on the congressional floor or behind office doors. Everything in the capital was (and still is) political, including its elite society. As late as 1923, one Washington newspaper was advising that the “astute” woman soon learned upon entering the capital that “if she would seek her husband’s political or official fortunes she must build her house of calling cards.”

Americans did not invent calling cards. British traveler John Barrow gave that honor to the Chinese. After an extended stay in Asia, he wrote in 1804 that “visiting by tickets which, with us, is a fashion of modern refinement, has been a common practice in China some thousand years.” By at least the eighteenth century, though, calling cards were not only prevalent in China, but a prerogative of the upper classes around Europe. In 1884, historian Horatio F. Brown discovered a cache of Venetian calling cards at a local museum, ranging in date from the end of the sixteenth century into the nineteenth century, and in the 1840s, workmen renovating a marble chimney-piece in Soho found the calling card of Sir Isaac Newton, dead since 1727.

Colonists brought the practice with them to the New World and by the Federalist period, elite American society was carding as if it had created the custom. Martha Washington used calling cards and kindly left a few for history, along with her calling card case, while New Englander Timothy Dwight found the topic prose-worthy. In 1794, the reverend penned his pity for those “dames of dignified renown” who with their “debt of social visiting to pay,” were “forc’d, abroad to roam . . . To stop at thirty doors, in half a day, Drop the gilt card, and proudly roll away.”

If gilt cards were the fashion in 1794 (Martha Washington’s visiting card was plain with her name handwritten across the middle), a century later they most definitely violated society’s strict rules of simplicity. The best cards, instructed one etiquette book, were “fine in texture, thin, white, unglazed and engraved in simple script without flourishes.” Trendy styles such as “gilt edges, rounded or clipped corners, tinted surfaces or any oddity of lettering” were to be avoided, and ornamentation or a photographic image on the card savored of “ill-breeding.”

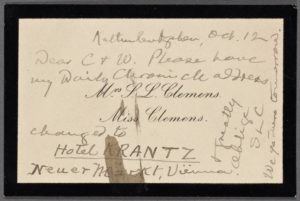

Although the style of a card may have fluctuated over the course of the nineteenth century (at least among the ill-bred), its basic structure changed little. Women carried cards about three and a half by two and a half inches, often in a special case. Men carried smaller cards, which were better suited for a breast pocket. Younger women with shorter names sometimes used square cards. The street address, but not the city, was occasionally engraved on the lower right-hand side, although such an addition was rarely needed until the late 1800s. Those either new to the city or visiting wrote their temporary residence on the card.

A daughter of visiting age had no card of her own. Her name, instead, was printed on her mother’s card. Single women “of a certain age,” who were clearly independent and without need of a chaperone, carried their own cards. A married woman identified herself by her husband’s given name, “Mrs. George Smith,” but never by his professional title, “Mrs. Dr. George Smith.” In addition, those few women who had earned their own professional titles were discouraged from using them socially, including on their visiting cards.

A divorced woman used either her own first name with her former husband’s surname or reverted to her maiden name if no children were involved. Either way, the woman remained a “Mrs.” for life. A widow used her first name on her calling card only if not doing so caused confusion—for example, if her husband’s namesake son, John Phillips Jr., dropped the suffix after his father’s death, leaving both his wife and his mother “Mrs. John Phillips.” Otherwise, a widow clung tightly to her husband’s full name on her visiting card, partly to maintain her prestige and partly to identify herself as a widow and not a divorcée. Widows sometimes added a thin black border around their cards, although anything over a quarter of an inch tinged on “ostentation rather than affliction.”

In 1888, the Good Housekeeping Fortnightly Journal dared to question the logic of a social system that required women to function under their husbands’ names. “Why should a woman sink her personality, as in Mrs. Arthur Thorne?” wrote feminist writer Hester Poole. “She wears neither his coats, hats nor boots; why wear his name? Is not Mrs. Agnes Thorne, equally euphonious and more expressive? Does she cease to be Agnes because she has married Arthur?” It was a call for female equality that etiquette advisors ignored. A woman, they insisted, might be Mrs. Samuel Hunter Tarkington Smith or, to compromise, Mrs. S. H. Tarkington Smith, but she was never Mrs. Sarah Smith—at least not in good society.

Timothy Dwight’s “thirty doors, in half a day” was not an exaggeration in nineteenth-century society, particularly at the start of each social season. The procedure went thusly. Armed with her well-stocked card case and her list of calls, the lady set out on her afternoon rounds (called by society “morning calls”). At each door, the visitor presented the answering servant with an exact number of cards—normally one of her own for the mistress and two of her husband’s for the master and the mistress. For many arbiters, leaving three cards was the maximum of good taste. To the servant, the lady might say, “For Mrs. B., please,” or “For Mrs. B., and I hope she is quite well,” with neither the expectation nor the wish of admittance, although one had to be careful in Washington. Except at the White House, where a card was left at the beginning of the season with no expectation of admittance, it was never quite proper, except among diplomats and those who “go out a great deal,” to leave a card without inquiring if the mistress was receiving.

Household servants were well trained to accept calling cards at the door, perhaps with a small tray in hand. Visitors placed their cards on the tray and departed, or if staying for a visit, were escorted into the sitting room. Ladies never handed their cards directly to the mistress. If a household received a card by post, an acceptable custom under certain conditions, it was removed from its envelope before being placed on a hall tray. The cards that gathered on the front table provided evidence of one’s social standing and visual reminders of reciprocal responsibilities.

It was sometimes the fashion to fold one’s card in order to indicate the purpose of a visit, particular folds indicating particular types of visits. A crease in the upper left indicated a social call; one in the upper right, a visit of congratulations; in the lower right, a visit of sympathy. If one were leaving town, he or she folded the lower left of the card. Mark Twain poked fun at the practice in The Gilded Age, warning his Washington protagonist that she had better take care “to get the corners right,” otherwise, she might “unintentionally condole with a friend on a wedding or congratulate her upon a funeral.”

Twain’s precaution was not far from the truth. Rules for card folding varied, particularly in Washington, where etiquette authorities writing during the last quarter of the nineteenth century gave their readers conflicting advice. Mary Logan subscribed to the method given above. Madeleine Dahlgren counseled those departing the capital to write P. P. C. (pour prendre congé, to take leave) on their cards instead of folding a corner and to turn down the upper right-hand corner (not the left one) to indicate a social call. DeB. Randolph Keim insisted that card folding was practical but not in general use.

Keim’s advice kept more with what was becoming the national trend by the late 1800s. In place of card folding, someone leaving town might print P. P. C. (as Dahlgren had suggested) in the lower left-hand corner of his or her card. For condolences, cards might be delivered with no folds, or if the family was on familiar terms, with a handwritten “deepest sympathy” added below the engraved name. Cards left in response to happier occasions, such as the birth of a child, might more routinely include a handwritten “hearty congratulations.” Questions, however, on what to fold or not to fold continued into the twentieth century. That century’s premier etiquette authority, Emily Post, warned her readers that the folded corner on a received visiting card might indicate that the one card was “meant for all of the ladies in the family” or it might mean that the card was left personally at the door, or she added, it might “mean nothing whatever.” Nevertheless, whatever the fold or the reason, Post commented, “more visiting cards are bent or dog-eared than are left flat.”

In any city, the leaving of cards was most hectic at the start of “the season,” when visits were made to the homes of everyone in one’s social circle. Outside of the capital, the winter social season might open with the opera, as it did in New York. In Washington, the season originally coincided with the opening and closing of Congress, most often from the beginning of December until the first week of March. By late century, DeB. Randolph Keim was describing three different seasons: one initiated in October by the families of the Supreme Court, resident officials, and local society as they returned from their summer retreats; a congressional season that began the first week of December; and an “official” or “fashionable” season that began with the presidential and cabinet receptions on New Year’s Day. Washington’s social season in any form ended, as it did elsewhere, with Lent, followed in the capital by a “little season” that lasted until “the first furnace blast” of summer drove even the most faithful to cooler climates.

One did not randomly knock on doors at the beginning of each season. Except in the capital, wealth and longevity determined the order of these initial visits. One called first on the most established, respected matriarchs, usually after a formal introduction or with a letter of introduction in hand. She then returned the call within a week or ten days. After that, no further visiting was required unless mutually agreeable; and, of course, all of this could be done through servants and cards. In Washington, official rank decided what doors were knocked on first and by whom. Prior introductions were unnecessary, and, given capital society’s constantly changing faces, impractical. A shorter turn-around time was expected, but as elsewhere, once cards were exchanged, further visits between the parties were optional.

In any city, one could drop off cards without asking to be received, although Washington was least prone to that custom. Nowhere was it proper to simply leave a card at the door if, at that hour, the mistress was conducting her weekly reception. Such days were a standard of the social season and often noted on a woman’s calling card. In many cities, women coordinated their reception days by neighborhood. In Washington, where political distinction determined at-home or “drawing room” days, vice-presidential wife Abigail Adams had struggled to figure out the best day for her drawing room, but by mid-century, a well-established rhythm had taken over. The wives of the Supreme Court and the residents of Capitol Hill opened their homes each Monday afternoon. Wives of the House reserved Tuesdays. Wednesday went to the wife of the vice president and the cabinet wives. Senatorial wives claimed Thursday, and Friday and Saturday went to Washington residents without a pre-scheduled day. The wives of the commandant and officers of the Navy Yard determined their own reception days.

The earlier first ladies varied their drawing room day according to their preference. Martha Washington and Abigail Adams gave theirs on Friday evenings for mixed company. Their husbands held separate Tuesday receptions, for gentlemen only, but attended the Friday gatherings as guests. Jefferson had no wife and no interest in a weekly reception of any type. Dolley Madison famously oversaw her Wednesday evening “squeezes” and her husband forewent a separate reception. Evening receptions soon gave way to afternoon events at which the first lady officiated without her husband, usually on Saturday afternoons. Unfortunately, as the century progressed, these events grew massive in attendance. Whereas Dolley Madison had admirably entertained between 200 and 300 guests a week, Frances Cleveland oversaw, on one such occasion, 4,000 men, women, and children, all there to shake the hand of the president’s wife. Her successor, Ida McKinley, did not have the good health needed for such a grueling routine, and her omission of a weekly “card reception” was the beginning of its demise at the White House.

Official rank ruled Washington and always determined who called on whom first. The president received first calls from everyone and did not return calls except to visiting sovereigns, a practice established by George Washington and continued undisturbed by every president after. Like their husbands, first ladies always received the first call, but unlike their husbands, the earlier ones made reciprocal visits to at least those in their immediate social circle. That ended with Elizabeth Monroe, who flatly refused to oblige. The task, she insisted, was too arduous for someone in her fragile health and, moreover, the city had grown too large in population for such an accommodation. Washington society begrudgingly accepted the inevitable, although it continued to bristle whenever other White House women, even those serving as surrogate first lady, refused to make return calls.

The vice president called first only on the president, but, unlike the president, he made return visits. The Supreme Court justices called first only on the president and the vice president. The Speaker of the House called first on the president, vice president, and justices; senators made first calls on those gentlemen and on the foreign ministers. Senators received first calls from the cabinet and the cabinet received first calls from foreign ministers. House members, other than the Speaker, eventually fell to the bottom rung of the hierarchy, ranking below senators, justices, the cabinet, and foreign ministers. They called first on everyone. Wives and daughters had the same social status as their husbands and fathers and kept to the same rules, except that the ladies of the cabinet called first on ministerial wives, and not the reverse.

Early in his presidency, George Washington established a written “Line of Conduct” for use during his administration. It explained his office hours, his intent not to return calls, and his entertainment schedule, which included the Tuesday and Friday receptions and a Thursday dinner for “as many as my table will hold.” The Adamses kept to the same protocol, but Jefferson initiated a more republican version, eliminating the weekly receptions and opening his door more widely to visits. Unlike with Washington’s “Line of Conduct,” Jefferson’s “Canons of Etiquette” established protocol not only for the president but also for those associated with his government, which in the young capital was almost everyone. The canons instructed the city on everything from the order in which to make official first calls to proper seating at dinners and public functions (first come, first served), and it aimed to eliminate what Jefferson considered monarchical protocol. “When brought together in society,” read one tenet, “all are perfectly equal, whether foreign or domestic, titled or untitled, in or out of office.”

The city understood Jefferson’s rules as the political statement they were. They were barely followed while he was in office and mostly ignored after he left. The one tenet that Washington society did not ignore was Jefferson’s directive that “Members of the Legislature . . . have a right as strangers to receive the first visit,” meaning that cabinet wives needed to make first calls on all the wives of Congress. With the hospitable Dolley Madison as lead cabinet wife and a provincial capital that saw only a handful of congressional women each session—Jefferson counted nine such ladies in 1807—the president’s edict was not a problem, but fifteen years after the canons, Congress was 25 percent larger, the city was more inviting, and family housing was more available. With that came a major increase in the number of wives who joined their legislative husbands in Washington for the social season. So much so that Louisa Catherine Adams, wife of Monroe’s secretary of state, John Quincy Adams, refused to make first calls on the congressional wives, arguing that their number had grown too vast. The congressional wives retaliated by snubbing Mrs. Adams’s drawing room and dinners, and when John Quincy Adams followed his wife’s lead, he found himself chastised by an offended Senate.

What followed was months of public debate between the executive and legislative branches. The Senate invoked the spirit of Jefferson, telling John Quincy Adams that their insistence on first calls came not from pretension, but from their position “as strangers.” The congressional wives went to Elizabeth Monroe with their complaint and used the same logic. As strangers arriving to the capital, they were entitled to a first call from all of the cabinet wives, and Mrs. Adams had refused to oblige. In response, Elizabeth Monroe quite literally summoned the secretarial wife to her chambers. The congressional ladies “had taken offence,” she explained, and she hoped that the situation might be rectified. But Louisa Adams was unmoved. She held a weekly drawing room, gave dinners, and returned calls. To also make first visits on every lady arriving to town as a stranger, congressional or otherwise, was a massive undertaking to which she would not commit.

Unable to rely on the White House, the women of Congress dealt with Mrs. Adams by snubbing her entertainments. Even a year after the quarrel began, Louisa Catherine reported that at one of her drawing rooms, “only two Ladies attended and about sixty gentlemen.” At another entertainment, to which “Mrs. Adams invited a large party,” guest Sarah Seaton was surprised to find “not more than three ladies” in attendance. With time, though, the women forgave her, particularly after it appeared she might become the next first lady. In December 1822 she wrote that only one lady of the Congress still refused to make the first visit, senatorial wife Elizabeth Dowell Benton, whose husband was, according to Louisa Adams, the “inflexible enemy of Mr. A.”

Calling card etiquette, capital-style, was beginning in earnest. The Adams incident showed carding to be a game that the women of Washington refused to take lightly, and rightly so. This was the nation’s capital, built for a single purpose. Everything there commingled with national politics, including its etiquette. When the congressional wives pressed for first visits, they did so knowing the importance of the city’s social-political hierarchy. Who called on whom first was a direct reflection on where they stood in that hierarchy. With the right social standing came status, respect, and beneficial alliances, not only for themselves but also for their husbands, for their children, for the family name, and, in many cases, for their communities back home. Moreover, thanks to the century’s well-defined gender roles, capital society’s social interaction, laced as it was with domesticity, virtue, and civility, was the one Washingtonian arena accepted as the domain of its women. It was a responsibility that they readily accepted because with it came autonomy and an informal power. Far into the next century, these women would yield to no man their right to run Washington society as they saw fit, and no one would prove that point better than the otherwise indomitable “Old Hickory.”

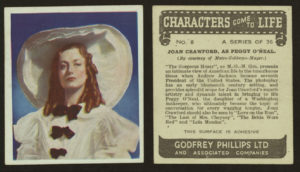

In the months before Andrew Jackson’s inauguration, Margaret O’Neale Timberlake Eaton, the bride of incoming secretary of war John Eaton, left her calling card at the home of Floride Calhoun, wife of the vice president. Peggy O’Neale was the attractive daughter of a respectable Washington City innkeeper, but she carried with her a reputation for being too “willing to dispense her favors wherever she took a fancy.” At seventeen, she had married navy purser John Timberlake. When Timberlake died at sea, rumors spread that he had committed suicide after learning of his wife’s indiscretions during his absence, including an affair with widower John Eaton, a close friend of Andrew Jackson.

Timberlake’s marriage to cabinet appointee Eaton placed her at the center of Washington society, at least on paper. In reality, the women of that society balked at admitting Peggy Eaton into their circle, none more so than Floride Calhoun, who pointedly ignored Mrs. Eaton’s calling card and refused to make the customary return visit. The other cabinet wives and elite women of Washington followed in kind. No harsh words were spoken. The calling cards, or lack of them, on Peggy Eaton’s front table did all the talking. Mrs. Eaton was not welcome in capital society.

Andrew Jackson was aware that Washington gentility disapproved of the new Mrs. Eaton, but he refused to heed the rumors. The president remembered Peggy O’Neale from his days as senator and had always liked her. Furthermore, Jackson linked the current public gossip to the previous defamation of his late wife during the 1828 presidential campaign, seeing in society’s reaction to Peggy Eaton the same backbiting and malice that had followed his wife. Determined that she should be both accepted and respected, Jackson intervened in her defense by ordering his cabinet members to tend to their wives. When the secretaries refused, he wiped his cabinet clean—accepting voluntary resignations from John Eaton and Secretary of State Martin Van Buren and forcing resignations from the rest, keeping only Postmaster General William Barry, whose wife, it should be noted, had accepted Peggy Eaton into her private social circle. With that, according to historian Catherine Allgor, the women of Washington retreated into their homes, horrified by the consequences of their actions.

The women of Washington, though, had not surrendered. They may have been bloodied by battle, but they had decidedly won the war. Peggy Eaton not only left the cabinet circle, she left town, moving first to Tennessee, where her husband made two failed attempts at a Senate seat, and then to the outposts of Florida when Jackson appointed Eaton territorial governor. And despite Jackson’s blustering, the men he appointed to his second cabinet all had wives of “the right stuff,” women who were established members of polite society and pillars of virtue.

The most repeated challenge to protocol, however, came not from outside the ranks of those in charge of official society, but from inside. It centered on the recurring argument between cabinet and Senate wives as to who should call on whom first. Although the 1820s saw the ladies of the House, like their husbands, move to the bottom of the social hierarchy, Senate wives still expected the honor of a first call from the women of the cabinet (Louisa Catherine Adams aside). The logic now, according to those women, was that their husbands represented “state sovereignty,” a dignity superior to that of any appointed officer.

Since there were only a handful of cabinet wives, but dozens of senatorial ones, the ladies of the cabinet never found that argument very persuasive and occasionally attempts were made to reverse the protocol. One who tried was Kate Hughes Williams who, immediately after her husband’s appointment as attorney general in 1871, announced that she would not be making first calls on the Senate wives. As historian Kathryn Jacob observed, “After four years as a Senate wife herself, Mrs. Williams should have known better.”

Kate Williams, though, had reigned in Washington during her husband’s Senate years and mistakenly believed herself to have influence over protocol. Unfortunately, she stood alone among the other cabinet wives, and the senatorial wives refused to make the first call on her. Two years later, when President Grant nominated her husband to the Supreme Court, those same Senate women refused to protect Williams against accusations made during the confirmation hearing of her various “peccadillos.” Indeed, at least one local matron attributed George Williams’s eventual failure to win the judgeship as the direct result of “Mrs. Williams’s arrogance toward the wives of the Senate who joined [one of the committee members] in his determination to humiliate Mrs. Williams” and defeat her husband.

The fight between cabinet and Senate wives erupted again after Congress passed the Presidential Succession Act of 1886, which placed the various cabinet secretaries in direct line for the presidency. Since the secretarial wives now considered themselves possible mistresses of the White House, they asserted a claim of precedence. Not so, retorted the Senate wives. “Until a cabinet officer becomes President he is still the creature of the Senate, and his wife must make the first calls, as heretofore.” The following social season began with the two sets of women deadlocked, but on January 17, the Jamestown Evening Journal proclaimed the Senate wives “triumphant.” Mary Manning, bride of the secretary of the treasury (and a key instigator according to one newspaper), had led the way to reconciliation by beginning her round of first calls only the day before. “It was an uneven fight at best,” the Journaldecided, “for it must be remembered there are 76 senators and only 7 cabinet officers.”

The capital would continue to build its political and official fortunes on a house of cards long after the system had loosened its grip on other cities, and always with its women firmly in command. There is an adage that it is not what you know but who you know that matters. Nothing was truer in nineteenth-century Washington, where one’s sources of influence were limited to reputation, political stature, and personal interaction, and no one had more access to that last form of influence than the ladies of the city. The Senate wives who continued to demand first calls from the cabinet women, the cabinet wives who refused to allow even a president to tread on their domain, and the women who daily stepped into carriages to knock on thirty doors—and then thirty more—did so out of an understanding that carding as a form of social networking was also a form of power, not only for their husbands, but for themselves.

Further Reading

The best way to learn about Washington’s nineteenth-century calling card society is through the women who built it, beginning with the Diary and Autobiographical Writings of Louisa Catherine Adams, edited by Judith S. Graham (Cambridge, Mass., 2012). Other invaluable works include Margaret Bayard Smith, First Forty Years of Washington Society, edited by Gaillard Hunt (New York, 1906), Selected Letters of Dolley Payne Madison, edited by Holly C. Shulman and David B. Mattern (Charlottesville, Va., 2003), Josephine Seaton’s William Winston Seaton of the “National Intelligencer”: A Biographical Sketch, which contains many letters by his wife, Sarah (Boston, 1871), and Mary Simmerson Cunningham Logan, Reminiscences of a Soldier’s Wife (New York, 1916). Logan also wrote Home Manual: Everybody’s Guide in Social, Domestic, and Business Life with two chapters on Washingtonian protocol (Boston, 1889). Logan was a Washington insider, as was social arbiter Madeleine Vinton Dahlgren, Etiquette of Social Life in Washington(Philadelphia, 1881), and De Benneville Randolph Keim, Hand-Book of Official and Social Etiquette and Public Ceremonials at Washington (Washington, 1889). Two other excellent late-century etiquette books are Florence Howe Hall, Social Usages at Washington (New York, 1906) and Maud C. Cooke, Social Etiquette, or Manners and Customs of Polite Society, with a chapter on Washington (Buffalo, 1896). The earliest book of its kind comes from E. A. Cooley, Description of the Etiquette at Washington City (Philadelphia, 1829). Note that some of the above nineteenth-century titles have been shortened to manageable lengths.

George Washington’s “Queries on Conduct” (May 10, 1789), and Jefferson’s “Rules of Etiquette” and “Canons of Etiquette to be Observed by the Executive” (December 1803), can be found online at the Library of Congress and in several book editions of their respective papers; the Philadelphia Aurora General Advertiser published a third version of the canons on February 13, 1804. Kathryn Allamong Jacob, Capital Elites: High Society in Washington, D.C., After the Civil War (Washington, D.C., 1995), and Catherine Allgor, Parlor Politics: In Which the Ladies of Washington Help Build a City and a Government (Charlottesville, Va., 2000), offer additional insights into Washington’s nineteenth-century elite society, as does Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner, The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today (Hartford, Conn., 1873). For a British perspective, see Leonore Davidoff, The Best Circles: Society, Etiquette and the Season (London, 1973).

Merry Ellen (Melly) Scofield is an assistant editor with the Papers of Thomas Jefferson at Princeton University. Her research centers on nineteenth-century social Washington and includes work on Thomas Jefferson’s dinner parties, the reign of Dolley Madison, and the first ladies of the Cleveland and Benjamin Harrison administrations.